The towering skyscrapers of our cities hide an invisible landscape of immense value - not in their steel frames or glass facades, but in the discarded electronics accumulating in their shadows. This urban mine, composed of obsolete smartphones, dead laptops, and defunct hard drives, contains concentrations of rare earth elements that often exceed those found in traditional ore deposits. As the world grapples with supply chain vulnerabilities for these critical materials, green chemistry innovations are transforming how we recover valuable metals from electronic waste.

Behind the sterile terminology of "urban mining" lies a radical reimagining of waste streams. Where conventional mining operations move mountains to extract fractions of a percent of target minerals, e-waste processors sift through material that already contains refined and purified metals. A single ton of random circuit boards yields more gold than 17 tons of gold ore, while rare earth magnets in hard drives contain neodymium concentrations 10-20 times higher than primary deposits. The challenge has never been availability, but rather developing extraction methods that don't create new environmental burdens while solving existing ones.

Traditional rare earth recovery methods resemble medieval alchemy more than modern materials science. Smelting shredded electronics releases toxic brominated flame retardants into the atmosphere, while acid leaching generates lakes of hazardous sludge. "We're seeing a paradigm shift from brute-force pyrometallurgy to molecular-level precision in metal recovery," explains Dr. Elena Marquez, a materials chemist at the Singapore Urban Mining Initiative. Her team's work on selective ionic liquid extraction demonstrates how tailored solvents can pluck specific rare earths from complex waste streams without the environmental toll of conventional approaches.

The green chemistry revolution in e-waste processing hinges on three fundamental principles: selectivity, renewability, and circularity. Advanced membrane technologies now separate rare earths based on atomic radii differences as small as 0.01 nanometers. Bioengineered proteins derived from rare earth-absorbing bacteria show promise for "fishing" specific metals from solution. Even humble cellulose from agricultural waste is being transformed into nanostructured filters that trap europium and terbium while letting other elements pass through.

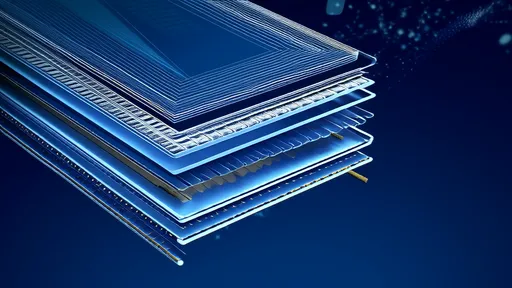

Industrial symbiosis is turning waste streams into supply chains. In northern Japan, a former hard drive factory now serves as a rare earth recovery hub, using precisely tuned organic acids to dissolve magnets from obsolete data center equipment. The process yields 99.9% pure neodymium with 80% less energy input than virgin metal production. Meanwhile, Belgian researchers have commercialized a photochemical method that uses sunlight-activated catalysts to selectively recover indium from LCD panels - a process that simultaneously generates hydrogen as a byproduct.

Policy landscapes are struggling to keep pace with these technological advances. While the EU's recent Critical Raw Materials Act sets ambitious recycling targets, many Asian and African nations handling the bulk of global e-waste lack infrastructure for advanced recovery. "We're seeing a dangerous dichotomy emerging," warns environmental economist Dr. Kwame Osei. "High-value rare earth recycling happens in high-tech facilities of developed nations, while crude dismantling operations in developing countries bear the environmental costs without capturing the material benefits."

The economic calculus of urban mining is shifting dramatically. Where once only gold and copper recovery made financial sense, new processes have made 17 rare earth elements economically viable to reclaim. A 2023 MIT study calculated that comprehensive e-waste recycling could supply 40% of global rare earth demand by 2035, potentially stabilizing the volatile markets that currently leave manufacturers vulnerable to geopolitical disruptions. Automotive companies are particularly invested, with electric vehicle makers securing urban mining partnerships to ensure magnet supply for millions of planned motors.

Consumer behavior remains the weakest link in this emerging circular economy. Despite growing awareness, global e-waste collection rates hover around 20%, with the rest languishing in drawers or landfills. Innovative collection schemes - from Amazon's trade-in drones to Ghana's motorcycle-based "e-waste taxis" - are attempting to bridge this gap. The most successful models combine convenience with transparency, allowing consumers to track how their old devices become part of new products.

As the field matures, researchers are confronting unexpected challenges. Certain rare earth combinations in newer electronics prove more stubborn to separate than legacy components. The miniaturization trend means less material per device to recover. Perhaps most surprisingly, some urban mines are becoming too rich - smartphone processors now contain such trace amounts of gold that recovery becomes energy-inefficient, necessitating entirely new approaches to circuit board design.

The ultimate promise of urban mining extends beyond mere supply security. Life cycle assessments show that recycled rare earths can reduce the environmental impact of electronics by up to 90% compared to virgin materials. When combined with renewable energy to power recovery processes, the industry could achieve what once seemed impossible: high-tech manufacturing that actually reduces ecological footprints. As we stand at this crossroads, the choice isn't between technology and sustainability, but rather recognizing that our cities' forgotten electronics hold the keys to both.

In laboratories from Munich to Mumbai, the next generation of recovery technologies is taking shape. From CRISPR-edited microbes that bioaccumulate specific elements to quantum dot sensors that instantly characterize waste streams, the tools of molecular science are converging on the urban mine. What began as an environmental imperative is evolving into an economic opportunity and perhaps even a new industrial ecology. The metals we once buried are now rising from the waste stream, ready to be part of our technological future once more.

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025